I’ve recently seen and done a few incident investigations which really fell short of any mark except for ticking the box on the form that says ‘investigation completed’. There are ongoing debates about whether ICAM is better than TapRoot or if that is better than Root Cause Analysis or BowTie or Ishikawa. There are very few things in safety more simplistic, biased and subjective than ‘5 Whys’ or root cause analysis but I can understand the attraction.

As Rob Sams wrote recently in “Just Get to The Bottom Of It”:

Unfortunately, a mechanistic approach to investigating incidents constrains investigative thinking because factors such as the availability heuristic mean we must ‘just get to the bottom of it”, find those root causes, as quickly as possible.

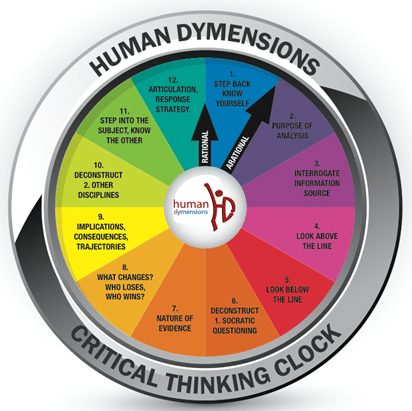

The result of using these simplistic tools is always predictable and usually just confirms the findings or outcome we originally wanted. With this in mind, the ‘CRITICAL THINKING CLOCK” has become one of my favourite tools, not only for incident investigations but for any other activity that requires critical thinking, analysis and articulation of ideas. Our current mechanistic tools only allow us to clamber over the surface of the iceberg tip – the reality being a focus on probably 4 o’clock and 12 o’clock with a very cursory pondering of all the other ‘times’. The critical first step is to ‘know yourself’, your personality type, how you learn, your biases and your agenda – these are things that initially prime, frame and steer your investigation, mostly unconsciously.

As Rob Long says in his article “Critical Thinking and Questioning in Safety”:

The beginning of ‘thinking differently’ about investigations and safety policy depends on stepping out of old boundaries and engaging in different worldviews about risk.

In the video below, Dr Rob Long, the creator of this tool, explains, better than i could, the basics of each step in this process. I hope you also find this method of thinking useful. Your thoughts would be much appreciated.

The ‘2 o’clock’ step asks us to interrogate the ‘Purpose of the Analysis’ and in that regard, this article from the SCM Safety Blog provides a fresh perspective:

There are plenty of resources out there designed to help us answer these questions. There are books, blogs, seminars, training courses and websites devoted to how to investigate an accident. We argue about the best methodologies that will give us the results we want and who should lead the investigation. We discuss what types of events should be investigated – is it just accidents or also other events (e.g., close-calls, near-misses)?

One of the puzzling things to us though is that with all of this discussion about how to investigate accidents there is very little discussion about why we investigate accidents. After all, accident investigations cost resources. Someone (or a group of people) have to take time out of their normal work schedule, stop producing whatever it is they normally produce, and conduct a proper investigation. Then the organization has to devote resources to fix whatever problems the investigators find. So investigations come with a cost. Are they worth it? Why do an investigation?

Now this probably seems like a trivial question to a few of you and we totally understand why – everyone knows that the reason to investigate accidents is to figure out what went wrong so you can prevent it from happening again.

Let’s look at this a bit closer. There’s a key assumption underlying this reason – accidents are caused by negatives that must be found and removed from the system (or prevented from having their effect). Something broke, someone failed in some way, etc. Therefore, the job of an accident investigation is to find the thing that broke (i.e., the root cause) and fix it (or replace it). Once fixed, the system is safe and the accident can’t happen again.

There are some problems with this line of thinking though. The idea that bad things are caused by something failing or breaking is something that works great for machines. If you’re trying to figure out why your clock stopped working you look for the part or parts that failed and fix/replace them. But, if we’re dealing with people and organizations, it doesn’t work that way. People do things that help them achieve success (or avoid failure). Therefore if someone does something that we say leads to an accident, to call that a failure or an error is often a very narrow and limited view.

To illustrate, lets use an example – someone worked on a piece of machinery without properly de-energizing it (i.e., locking it out). From the perspective of a safety professional that is a failure, because they failed to follow a rule. But the person didn’t do what they did because they wanted to fail. They acted in a way that they believed would help them achieve success in the environment they were in. Therefore, from another perspective, there was no failure.

The iTHINK CRITICAL THINKING CLOCK

iThink Critical Thinking Clock from Human Dymensions on Vimeo

In this video Rob introduces his iThink Critical Thinking Clock. The purpose of the video is to help people use a method that provides structure for deconstructing, interrogating, investigating and discovering in critical thinking about an issue or topic. The model of the clock implies the semiotic of time, a condition of reflection and critical thinking. Rob explains how two ‘sweeps’ of the twelve steps can help analyse, deconstruct and think more critically. The brief explanation is only introductory as a seminar introducing the model generally takes a few hours in a workshop. The idea behind this video is to introduce the model as a way of helping people begin to think about how they think about a topic. This model is effective for incident investigations and any other activity that requires critical thinking, analysis and articulation of ideas. For more information contact rob@humandymensions.com